- Home

- Simon Cheshire

The Poisoned Arrow Page 2

The Poisoned Arrow Read online

Page 2

‘I’ve got evidence,’ said Tom. ‘I’m not imagining this whole thing, you know.’

‘Ah,’ I said. ‘Evidence. OK. Give me your evidence.’

Tom leaned forward on my Thinking Chair. He glanced sideways, as if he expected to find half a dozen villains in black eye masks looming over his shoulder.

‘The play’s director, Morag Wellington-Barnes, is acting very suspiciously.’ He nodded slowly, wide-eyed, as if he’d just demonstrated the answer to a stunningly difficult maths problem.

I sighed. ‘Tom, that’s not evidence. That’s just you.’

‘She’s up to something,’ said Tom. ‘She’s been one of us Rackham Roaders for years, since before I joined, so I know her quite well. She’s gone very odd. Even odder than usual. She keeps losing her temper, biting her nails – revolting habit – and staring off into nowhere with a vacant expression on her face.’

‘Surely she’s just nervous?’ I said. ‘There’s every reason to be.’

‘You won’t say that when you meet her,’ said Tom. His nostrils flared into a semi-sneer. ‘I know I’m thought of as arrogant at school, it’s no use protesting . . .’

(He was right. I wasn’t about to.)

‘. . . I simply have high standards,’ said Tom, loftily, ‘but Morag Wellington-Barnes is more fearsome than a sergeant major in a platoon full of marines. However, she’s very good at organising plays, so everyone puts up with her. Obviously, whenever I’m involved in a play, I’m always coming up with superb ideas for improvements to scenes. She rarely listens to me at the best of times but at the moment she’s making one crackpot decision after another and nobody can change her mind.’

‘What sort of crackpot decisions?’ I asked.

‘Well, she’s reduced the cast, for one thing,’ said Tom. ‘The Poisoned Arrow has nineteen speaking parts – it’s quite a large-scale production – but she’s cut out eight of them. All the minor roles have simply been taken out. Madness! I feel sorry for Mrs Smoth – she was looking forward to playing Cackling Old Crone in scene six and now she’s out. She’s ninety-six, you know.’

‘Maybe Morag thought the play was too long or something?’ I shrugged.

‘Rubbish!’ cried Tom. ‘This play was a huge hit in London. Solid drama and excitement from beginning to end. If anything, it’s not long enough! And as well as that, Morag’s ruined the play’s whole staging. She’s scrapped all the lighting effects. Insanity! She’s insisting that the whole performance is done with the house lights up!’

‘The what-lights?’ I asked.

‘House lights,’ repeated Tom. ‘The lights where the audience sits. The ones that normally go out in a theatre or cinema when the performance starts, those are called the house lights. Morag is insisting they’re left on, right the way through the play! The atmosphere will be ruined!’

‘Hmm, well, yes, I guess that’s unusual,’ I said. ‘But she is the director. Isn’t that simply her approach to the play?’

‘I told you,’ said Tom, ‘she’s normally good at this sort of thing. Do these sound like good ideas to you?’

I shuffled uncomfortably. ‘You’re talking about, what’ya’callit, artistic differences. You say there’s crime involved, but there’s no crime whatsoever involved in what you’ve told me. And no, before you say it, a crime-against-the-theatre is not an actual crime!’

Tom shook his head. ‘You misunderstand me. I really do think there’s going to be an actual crime committed. A real, serious crime. Look, I have more evidence here.’

He pulled a couple of small sheets of folded-up paper from his pocket and handed them over to me. ‘I found these backstage,’ he said. ‘Someone had obviously dropped them by mistake but I don’t know who.’

Curious, I unfolded the first one. It was a plan of the theatre. It showed the road at the front of the building and the large open field at the rear (which was part of a neighbouring farm). It also showed three ways of getting into the theatre – the main entrance at the front, and two emergency doors (one to each side of the audience seating area). A set of large double doors, in the unseen-from-the-audience area behind the stage, were shown to open out on to the field, but they were marked:

These only open from inside. Their is no way in here.

‘Well,’ I said, examining the sheets more closely, to see if there were any clues to be had from the paper itself, ‘the only thing we can say for sure about this person is that they didn’t pay attention during English lessons. Their is no way ought to be There is no way. This first paper was torn from an ordinary spiral-bound jotter pad. Nothing unusual, and no [sniff!], no sign of perfume or aftershave. From the way they’re slightly crumpled and curved, I’d say they’d been carried in the back pocket of someone’s trousers.’

I unfolded the other sheet. It was slightly larger than the first, a printed list of twenty-two names, none of which I recognised. Five of them had an asterisk marked against them, and all twenty-two were followed by a letter and a number.

‘Are these people from the special guest list for Friday’s performance?’ I said.

‘All of them,’ nodded Tom. ‘The whole list is about sixty names long. Why these twenty-two should have been picked out, I have no idea.’ He pointed to the letters and numbers. ‘You see that? Some sort of code. I’ve been trying to make sense of it, but it seems random. B4, then against the next name there’s B28, then A2 . . . H16 . . . J7 . . . I31 . . . Can you work out what it means?’

A definite possibility crossed my mind. ‘Since we know that all these people will be at the play on Friday night,’ I said, ‘then, yes, I think I’ve spotted what this code means.’

Have you spotted it too?

‘I think this indicates the seats they’ll be sitting in,’ I said. ‘Row B, Seat 4, and so on.’

‘Ooh, of course!’ groaned Tom. ‘I should have realised.’

‘However,’ I said, ‘if these are seat numbers, then you’ve got a strange seating plan. These people must be dotted about all over the theatre. Aren’t you seating all your special guests at the front?’

Tom almost sprang out of the chair. ‘That’s another of Morag’s crackpot decisions,’ he cried. ‘I heard her and Sir Gilbert talking about it the other day. The guests had been allocated the seats at the front, but then Morag changed it. He was asking her why one of his friends had been plonked over by the toilets. She just got snotty with him and told him her decision was final. Mad!’

Then he almost sprang out of the chair again. ‘There! That settles it! This is evidence! Morag must have made that list!’

‘No,’ I said patiently, ‘it isn’t evidence, and anyone could have made this list. The seating plan is hardly a secret, is it?’

‘Hmm. No.’

‘I still don’t see any connection with any actual crime,’ I continued.

‘You won’t be saying that in a minute!’ said Tom. ‘The other day, after rehearsals, I was putting the costumes away so I was a few minutes late leaving the theatre. As I did so, I spotted Morag on the other side of the theatre’s car park. She was deep in conversation with a brutish-looking man, standing beside a shiny black Mercedes.’

‘Brutish-looking?’

‘He was built like a boulder and bald as one too. Even at a distance of about a hundred metres, I could see that half his nose was missing. And he had a huge scar down one cheek. He also had a bodyguard in dark glasses standing behind him and the bodyguard was built like three boulders stuck on top of each other! I’ve never seen such an obvious villain!’

‘Believe me, Tom,’ I scoffed, ‘there’s no such thing as an obvious villain. Don’t judge by appearances.’

‘I’ve played many a villain on the stage,’ said Tom loftily, ‘so I know what I’m talking about. That man was a villain.’

I was about to remind him that real-life bad guys aren’t quite the same as the ones in TV cartoons, but then I thought of something more important to say.

‘Could you hear what

they were talking about?’

‘Not from that distance, no. But I’m sure it was something relating to the theatre. Both of them kept looking over at it.’

‘Well, sorry, Tom,’ I said, puzzled. ‘I still don’t see any connection with any actual crime. What conclusion does all this point to?’

‘Oh, come on,’ scoffed Tom, ‘you’re the detective. Think about what’s happening on Friday evening. Add that to all the suspicious stuff I’ve told you about. Can’t you see the obvious possibility?’

Suddenly, I could. A cold feeling slimed up my spine.

Can you see what crime Tom was predicting?

‘How many people are going to be in the theatre in total?’ I gasped.

‘Well, sixty-ish invited guests, plus anyone else who’s bought a ticket,’ said Tom. ‘The place seats over five hundred in all and because Sir Gilbert’s appearing, it’s a sell-out.’

The cold feeling slimed up my spine all over again.

‘Someone could rob that entire theatre audience,’ I muttered in horror. ‘Turn up with a few heavies, block the exits. On Friday, that place will contain hundreds of people and they’re all going to have money with them. Ladies dripping with pearl necklaces, you said. They’ll be sitting ducks. It’d be like an old fashioned stick-’em-up. Good grief, it’d be a mass mugging!’

Tom went as pale as a slice of cheap bread. ‘Disaster! Calamity! And Morag’s up to her eyeballs in the whole despicable scheme! Do you think she’s hired a local gang or got some bad guys in from somewhere else?’

‘Wait, wait, wait!’ I cried. ‘Hang on, be sensible. We still can’t be sure about any of this. All we’ve got are vague suspicions and theoretical possibilities.’

‘But a robbery is a possibility,’ said Tom, ‘and you’ve got to admit these papers suggest that one is being planned.’

‘Maybe,’ I replied. ‘Only maybe. You say it’s evidence. Well, if it is, it’s the thinnest evidence I’ve ever seen. But I ought to have a bit of a dig around. Just in case. Can you get me into your next rehearsal? We don’t want to alert any villainous elements that might be around, so I could pretend to be interested in joining the Society, something like that?’

‘No problem,’ said Tom.

‘Good,’ I said decisively. ‘Never fear, Saxby Smart is on the case.’

A Page From My Notebook

(Scribbled under the covers, way after bedtime.)

I need to think about this carefully. From all that Tom has told me, a robbery IS a possibility . . .

BUT! Just because it’s POSSIBLE doesn’t mean it WILL happen – doesn’t even mean it MIGHT happen. We could simply be seeing a danger that ISN’T THERE AT ALL!

BUT! The decisions made by Morag the director COULD be interpreted in a sinister way:

• Her decision to cut down the number of people in the play COULD be an attempt to reduce the number of people who’d be backstage when the robbers turn up, thereby reducing the chances that someone, out of sight, might phone for help.

• Her decision to keep the house lights on COULD be a way to make it easier for the robbers to control the audience and spot anyone trying to escape.

• Her decision to place the guests all over the theatre COULD be a method to help the gang get to the wealthiest people quickly – gangster one takes this section of the audience, gangster two takes that section, and so on.

ON THE OTHER HAND, PART 1: Tom said that it was Sir Gilbert Smudge, the actor, who suggested the whole bring-along-your-money fund-raising idea in the first place. Could this mean that HE is the one who’s hatching a plot?

ON THE OTHER HAND, PART 2: We have no idea WHO drew that plan or printed that list. Tom only thinks it was Morag because he already suspects her of being up to something. Those papers could belong to anyone. And if they DON’T belong to Morag, then any suspicions of her start to look weaker . . .

. . . Unless several people involved in the production are part of a plot?

. . . Or am I jumping to conclusions? Are Tom’s suspicions totally unfounded, as I thought at first?

BIG QUESTION: WHO was the man with the scar? IS he involved? WAS Tom right to be alarmed? Or does the man have nothing to do with this business? What if he’s just Morag’s accountant or something like that? (Don’t forget: just because someone LOOKS villainous, doesn’t mean they are. I must stay fair and impartial!)

VITALLY IMPORTANT POINT: Where’s the MOTIVE (beyond running off with a load of money, I mean!)?

WHY would someone involved in the play want to wreck it? I need to concentrate on MOTIVE in my investigations . . .

I also need to get some sleep. Nighty night.

CHAPTER

FOUR

IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY, the old-fashioned, stick-’em-up bank robbery has become almost impossible. Security technology has become so good that the would-be thief has very little chance of getting away with anything like that any more.

So villains – serious, organised villains, I mean, not the grab-something-by-chance type – are becoming sneakier. Why not apply the principle of the traditional bank raid to new targets? Theatres, cinemas, offices, anywhere people might gather in numbers. A raid on The Poisoned Arrow would end up looting cash, phones, jewellery, whatever people happened to have with them.

Disturbing thoughts like this kept spinning around in my mind from the moment I woke up the following day. And the more they kept on spinning, the more worried I became. I began to understand why Tom had such an uneasy feeling about Friday’s performance.

The morning’s lessons were as painfully slow as an earwig pushing a brick up a hill. The voice of Mrs Penzler, our form teacher, seemed to slide into one long, droning sound, like the distant honking of a ship’s horn.

At last it was lunch break and after collecting a tray of something which looked like it had already been eaten a couple of times (‘It’s vegetable stew,’ whispered the kid next to me in the queue, and ‘Ohhh,’ I whispered back), I went to sit down next to my great friend Isobel ‘Izzy’ Moustique.

She was unwrapping the sandwiches in her packed lunch and flipping through a magazine. Izzy is St Egbert’s School’s number one Brain, as well as being the girliest girl you’re ever likely to meet. If it’s information you need, head straight for Izzy.

‘No,’ she said, glancing up from her magazine.

‘I haven’t said anything yet,’ I cried.

‘You don’t need to,’ she said, turning a page. ‘You’ve got that look on your face, Saxby.’

‘What look?’ I said, innocently.

‘That look which says, “I’m stuck on a case and I need your help again”,’ she told me, trying to squash down a smile.

‘Am I really that predictable?’ I mumbled. ‘Am I really so transparent and easy-to-read? Does my face really betray my every innermost thought?’

‘Yes,’ replied Izzy.

‘Oh. Well, anyway, I’m stuck on a case and I need your help again.’

‘No,’ she said. ‘Sorry, I’ve got a load of science homework to finish. And so have you, come to think of it! We’ll both be in trouble if it doesn’t get done.’

We chatted about school stuff for a minute or two, while I sniffed cautiously at the vegetable stew. I took the two pieces of paper Tom had given me out of my pocket and looked over them again.

‘What are those?’ asked Izzy.

‘Oh, nothing really,’ I said with a shrug. ‘Just possible clues leading to a serious crime which might engulf around five hundred people at the end of this week. Anyway, we’re both busy, as you say, so, er, I’ll see what I can find out for myself. Not a problem.’

I guessed it would be roughly thirty seconds before Izzy’s curiosity got the better of her. Twenty-six seconds later, after she’d glanced at the papers eight times, she finally blurted, ‘OK, what do you need to know?’

I told her about Tom’s visit to my shed. Then I handed her the mysterious list of names.

‘What I’m particu

larly interested to know,’ I said, ‘is why these twenty-two names should be on a separate list like this, and also what the asterisks against these five names might signify. Don’t worry about those letter-and-number codes, because I’ve worked out —’

‘They’re just seat numbers, obviously,’ said Izzy, examining the list.

‘Er, right, yeah,’ I said hurriedly. I finished the rest of my stew. It tasted better than it looked.

The bell went for afternoon lessons. Izzy pocketed the list and stood up.

‘If I’m late handing in my science homework,’ she said with mock annoyance, ‘I’m going to blame you.’

‘I knew you’d give in,’ I said grinning. ‘I can read you like a book.’

Once school was finished for the day, I caught up with Tom and we headed over to Rackham Road. Tom talked about the play – and about how brilliant he was in it – non-stop from the moment we left the school gates. By the time we arrived at the Turtle-Shell, my brain was beginning to boggle at the way one human mouth could produce so many words in so short a time.

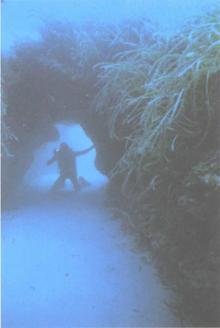

We entered the odd-looking building through the main entrance. Inside was a wide foyer and beyond that was the impressively large and rather cavernous auditorium. Its sides were lined with curtains, one or two of which were drawn back to reveal floor-to-ceiling windows which let in the last of the afternoon sunlight. Ahead of us was the stage, on which a dozen or more adults were milling about.

‘. . . so you can clash the swords together during the fights and they sound great, but they’re not dangerous,’ said Tom. He looked over at the stage. ‘Ah! The cast are all here. Well, now I’ve arrived we can begin the rehearsal.’

I quickly stuffed the white headphones I’d just taken out of my ears into my pocket. ‘Pardon?’

The Fangs of the Dragon

The Fangs of the Dragon Five Seconds to Doomsday

Five Seconds to Doomsday Underworld

Underworld The Eye of the Serpent

The Eye of the Serpent The Treasure of Dead Man's Lane and Other Case Files

The Treasure of Dead Man's Lane and Other Case Files Code Name Firestorm

Code Name Firestorm Project Venom

Project Venom Secret of the Skull

Secret of the Skull Operation Sting

Operation Sting The Hangman's Lair

The Hangman's Lair Airlock

Airlock The Pirate's Blood and Other Case Files

The Pirate's Blood and Other Case Files The Poisoned Arrow

The Poisoned Arrow Curse of the Ancient Mask

Curse of the Ancient Mask